The Devonian: The Age of Fish

About a Week and a half ago, my friend and I went fossil hunting at Red Hill, in the northern part of the state of Pennsylvania. It was a long drive: two hours and forty-five minutes, but it was well worth it. The last 20 minutes were through a forest on the edge of the Susquehanna River, which was nice, except for the many falls and rises. Finally we got there to meet Doug Rowe, the local paleontologist. He described a new species of early tetrapod, Densignathus, which I will talk about later. Red Hill is a large road cut in the Catskill formation, representing a teeming ecosystem living in what was once a flood plane full of narrow channels and oxbow lakes.

He led us to the Red Hill Field Museum, on the second floor of the Chapman Township Municipal Building. Full of fossils from the site, it was only two miles away. They also have fossils from other places, and I actually got to touch a Triceratops rib from the Hell Creek Formation. Here are some of the animals exhibited at the museum.

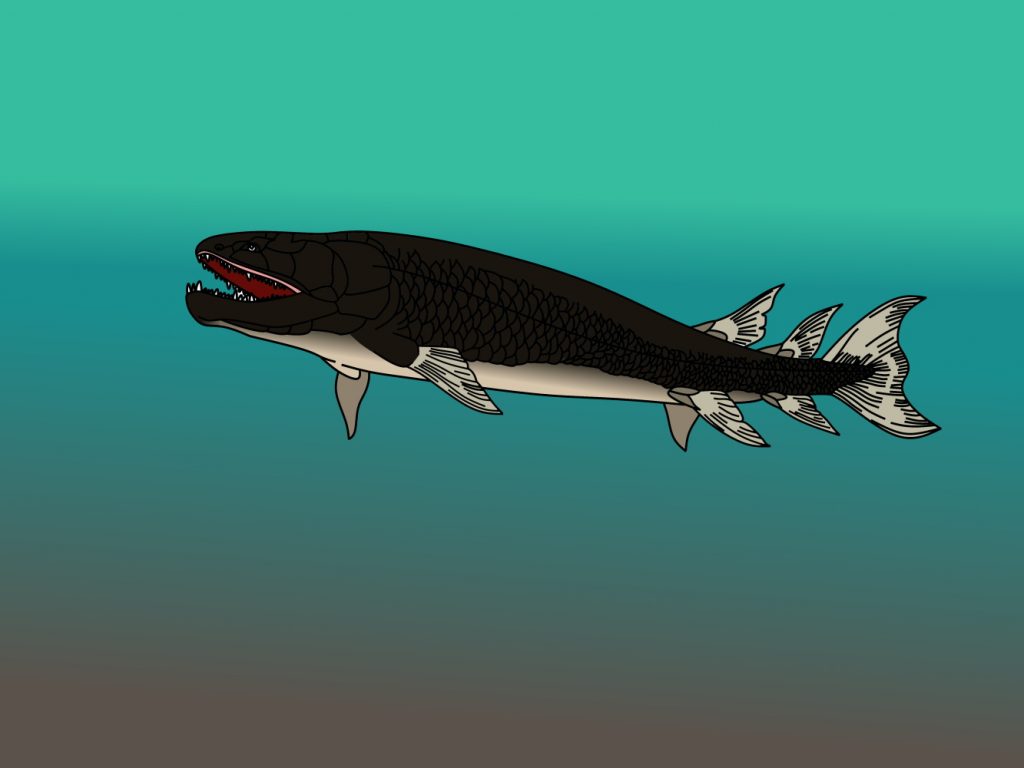

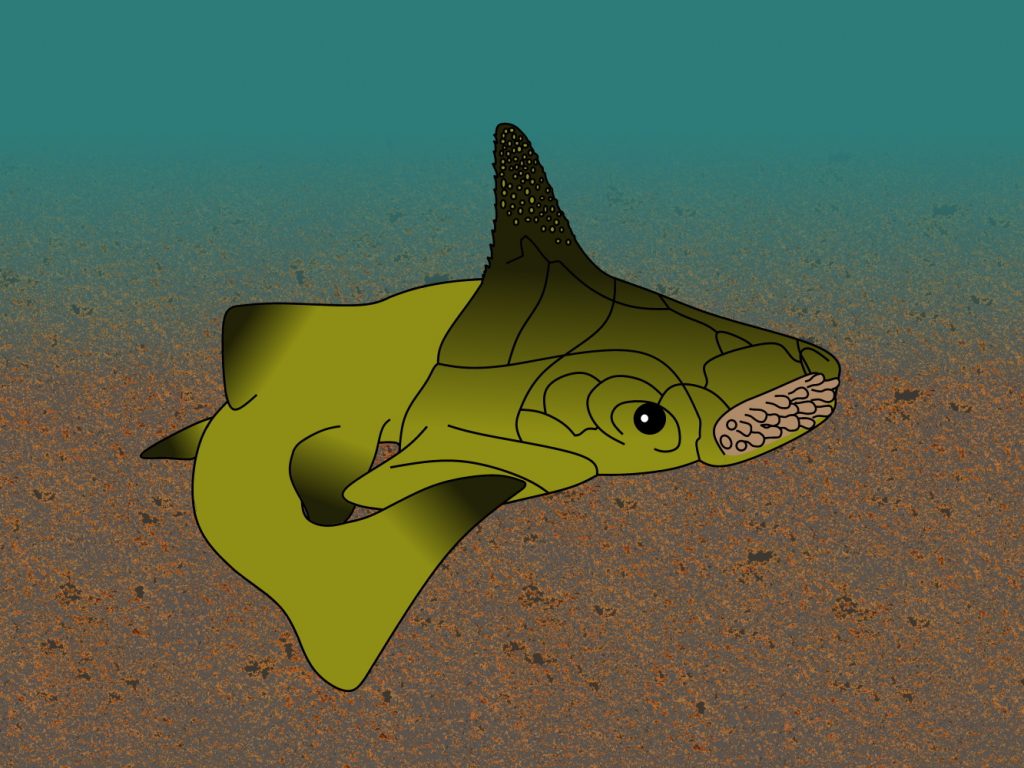

Hyneria

Hyneria lindae was a terrifying fish. It grew from 10-13 feet (3-4 meters) long, had a huge mouth full of multi-inch-long fangs, and it was a powerful swimmer. Thought to be the top predator of this ecosystem, it usually patrolled shallow channel margins. It is superficially similar to the more famous lobe-finned fish, Eusthenopteron. It might even be a larger species of this tetrapod-like fish, but because we don’t have the bones from around its eyes, it is hard to tell for sure. Its scales had characteristic frills where they connected to the body; You can see one of these in the picture at the top of this post. I found lots of these scales and several teeth on our trip there, as well as a few bones.

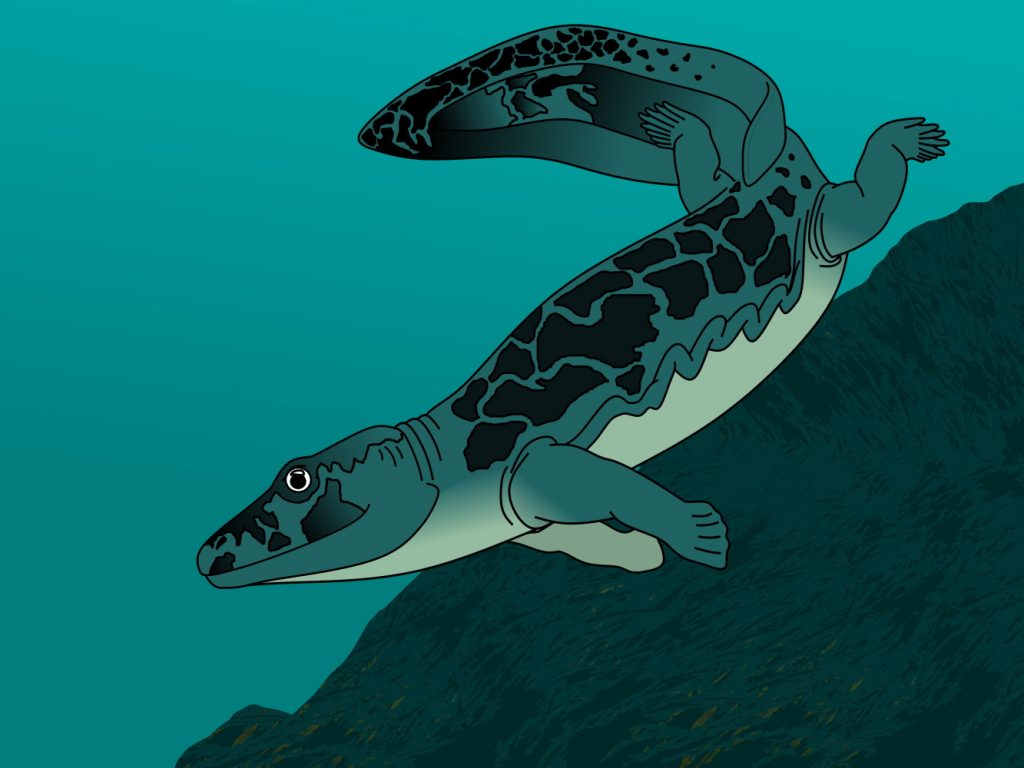

Hynerpeton

Hynerpeton basetti was one of the first tetrapods, and along with Hyneria, was the claim to fame of Red Hill. It was the first early tetrapod found outside of Greenland. It had stronger shoulders and lacked features found in gill-breathing fish or other early tetrapods like Ichthyostega and Acanthostega. It inhabited the shallow channel margins along with Hyneria, which probably preyed on it, considering Hynerpeton was only 3 feet (1 meter) long. (In case you were wondering, Hyner is a town not too far away from Red Hill.) One other identified tetrapod has been found at Red Hill, a more robust creature called Densignathus rowei.

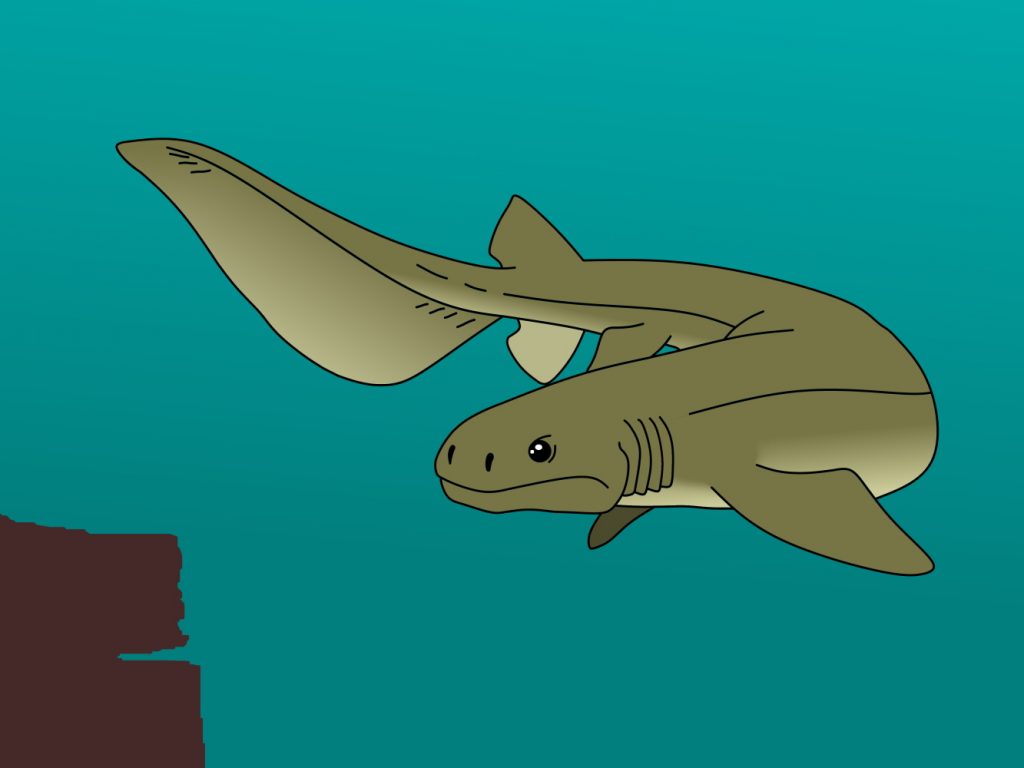

Ageleodus

Unlike Hyneria and Hynerpeton, Ageleodus pectinatus was found in one place other than Red Hill, a place in Poland. This early shark is only known from teeth (keep reading below to hear about the teeth I found), and most of these show very little wear, as they were replaced regularly by new ones. Red Hill has the most teeth of this genus than any other locality, and represent the earliest fossils of this shark. There was much variation in the number of cusps on the teeth, a challenge for scientists. It joined Hyneria and Hynerpeton in the shallow channel margins.

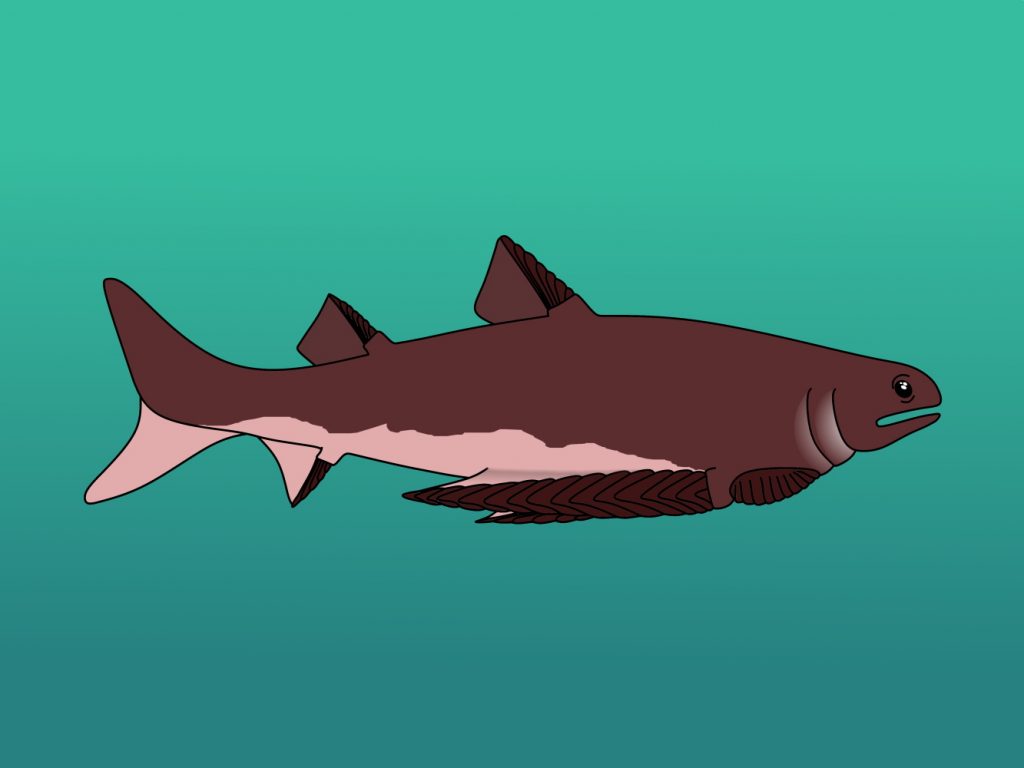

Gyracanthus

Gyracanthus was an acanthodian, a group of fish characterized by long spines that reinforced their fins. Gyracanthus lived in the shallow channel margins, and its near-triangular cross section countered the down-ward force of the tail. Gyracanthus‘ huge pectoral spines are thought to complement this shape, instead of being used for defense. These spines were roughly half the length of the animal, suggesting a maximum size of 4 feet (1.2 meters).

Turrisaspis

Turrisaspis is the second most common vertebrate at Red Hill, and grew to be 8 inches (20 centimeters) long. Its head and trunk, covered in a thick bony shield, are the only parts known from this fish. It lived in not only the shallow channel margins but also the floodplain pond, and was so common that there could be 20 individuals in 3 square feet (1 square meter), along with other species of fish. The long dorsal spine was reminiscent of the dorsal fins of most of today’s fish. It was closely related to the much more famous, and terrifying, Dunkleosteus.

What I found

Red Hill was the most productive fossil hunt I’ve ever been on, so I was surprised to hear that some of the people that hunted there barely found anything. After we went to the Museum, we headed back to the actual site. It didn’t take long for my friend to find two large Hyneria teeth in the rock face, which is silt stone. I found lots of fragments of this fish, including the scale at the top of this post. I found an imprint of a Gyracanthus spine. I found some good Turrisaspis spines, below, and some Ageleodus teeth. I was delighted later to find that a few of them were set in a bone, because we don’t have bones from Ageleodus.

I went close to where Hynerpeton was found and found a nice rock full of plant fossils and what I thought was a megalichthyidid scale. Than I went back to where I had found lots of Hyneria, nicknamed “Big fish alley”, and found a few more scales. Another member of our group found two huge Hyneria teeth in one rock, with no need for preparation. Soon after that, we started for home, laden with 360-million-year-old fossils. It was on the way home that we found out more about the place, and discovered the full significance of our finds, but the next day was even more exiting.

My friend emailed the next day that he had a Hynerpeton scute. Come to think of it, he had found it very close to where Hynerpeton was originally discovered, back in 1994. I was extremely exited for him; this was probably the rarest thing in his collection. Then, I remembered my hesitantly identified megalichthyidid scale.

It was half a week later that my friend and I identified my megalichthyidid scale as the left basal scute of Hynerpeton. He found he had one from the right; they may have been from the same animal. Later I studied the texture of my scute under the microscope and found it was quite bone-like, and it was complete except for the back half. It was the rarest fossil I had ever owned.

Here are some pictures of my best finds:

EDIT 11/28/22 – I have now known for a long time that this is not a Hyneria plate but a Groenlandaspis, a larger, rarer relative of Turrisaspis, after conferring with Doug Rowe.

EDIT 11/28/22 – This is not an ageleodus but a Gyracanthus spine.

Sources

http://www.devoniantimes.org/who/pages/hyneria.html

http://www.devoniantimes.org/who/pages/hynerpeton.html

http://www.devoniantimes.org/who/pages/densignathus.html

http://www.devoniantimes.org/who/pages/ageleodus.html

http://www.devoniantimes.org/who/pages/gyracanthus.html

http://www.devoniantimes.org/who/pages/turrisapsis.html

http://www.devoniantimes.org/who/pages/gillespiea.html

https://www.fossilguy.com/trips/redhill_may2014/index.htm

This Website is great! This site is very popular with residents of North Bend. I am planning on going there again soon.

the Red Hill site

The black plant is Ozinachsonia beerboweri, I think.

Thank you so much! I’m not very good with fossil plants.

LOL me neither I just looked at it on the Devonian Times website 😜😜

Digging up the past, I know you are very knowledgeable on Pennsylvania’s fossil placement. I was wondering what are fossils identified near Cumberland County? Any Dinosaur fossilization?

Hopeful Dinosaur Cloner, though there is knowledge of fossil species in the area, no extensive study of any formation/exposure has ever been conducted. The theropod Grallator and the ornithopod Anchisauripus are the only dinosaurs to have been noted in the county. There are several formations, such as the Ordovician Rockdale Run and Stonehenge Formations known only for the trilobite Bellefontia and others, Triassic Gettysburg Formation, where Grallator is from, and Cambrian Zullinger Formation, where stomatolites can be found. I can only say for certain that Cambrian, Ordovician, Triassic and Jurassic rocks are the only ones exposed anywhere in Cumberland County. As far as dinosaurs go, footprints are the mere account of their Pennsylvania existence. I have no direct locality in Cumberland available, but in Adams or York Counties there are exposures along several creeks in the area. The Little Conewago is supposedly the best…a paleontologist by the name of Robert Stahl set up a famous “Bone Bed” on the edge of it and found well preserved phytosaur jaws of the genus Rutiodon. I am wanting to head there myself! Happy Hunting,

Digging up the Past

These are cool fish

heck yeah!!

Can’t Believe that such amazing fish live in MY STATE!!!

I suggest an edit: “Gyracanthus” sherwoodi is a dubious species, potentially not Gyracanthus, instead a perhaps new species. thus put “Gyracanthus” in quotations.

References:

Snyder, D., Turner, S., Burrow, C. J., & Daeschler, E. B. (2017). “Gyracanthus” sherwoodi (Gnathostomata, Gyracanthidae) from the Late Devonian of North America. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 165(1), 195-219.