Welcome to the first Bringing Invertebrates to Life post! These posts are specifically designed for paleoartists interested in accurately reconstructing ancient invertebrates.

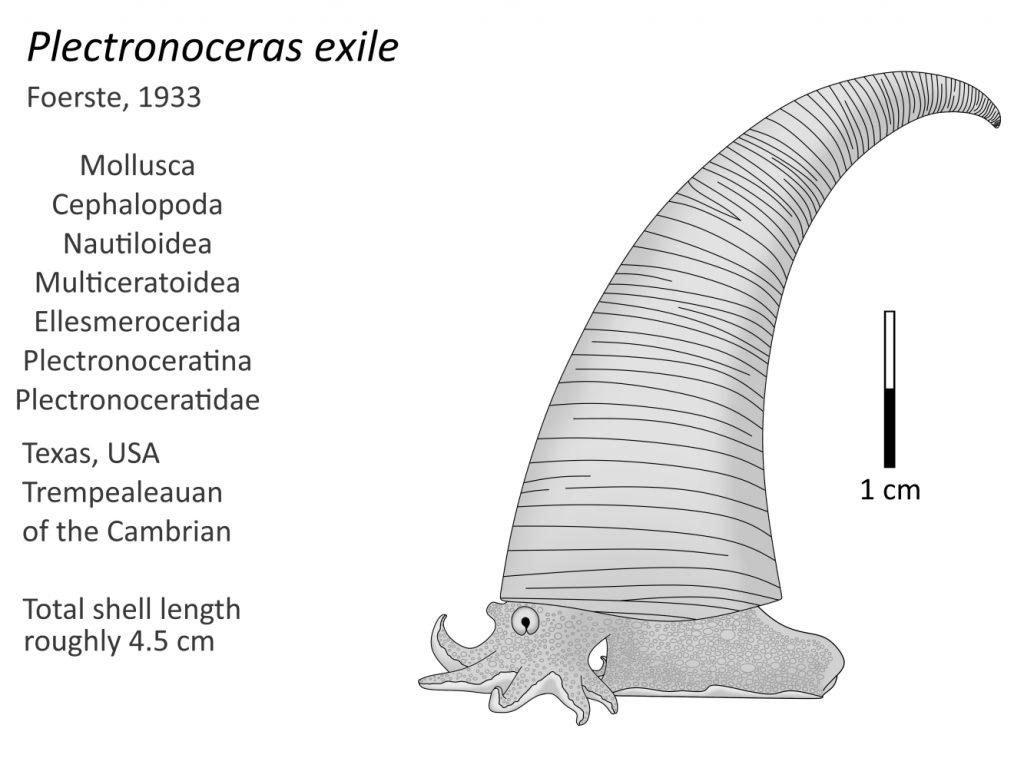

Plectronoceras was the earliest known cephalopod, living 504 million years ago. It was a small nautiloid, and while not well-known, there are a many reconstructions of it. In this post, we’ll look into how this animal looked, lived, and grew. And, of course, how to reconstruct it.

The Basics

All nautiloids, ammonoids, and quite a few coleoid cephalopods had a phragmocone, a shell divided into chambers by walls called septa. These chambers were filled with gas and liquid and were joined together by a soft tube called the hyponome. A shelled cephalopod would use its hyponome to regulate the amount of liquid in its chambers, changing the animal’s overall buoyancy. This lets the mollusk rise and fall in the water column, a huge advantage over other animals who have to actively swim to maintain their depth.

Plectronoceras was the earliest known animal to have a phragmocone, making it the earliest cephalopod as well. But what did the earliest cephalopods look like? To find out, we’ll have to meet the monoplacophorans.

Early mollusks

Monoplacophorans are mollusks that for a while were thought to be extinct. However, in 1952, several were found after a deep-sea dredge. Much research has been done on them since, so we have a very good picture of what they look like.

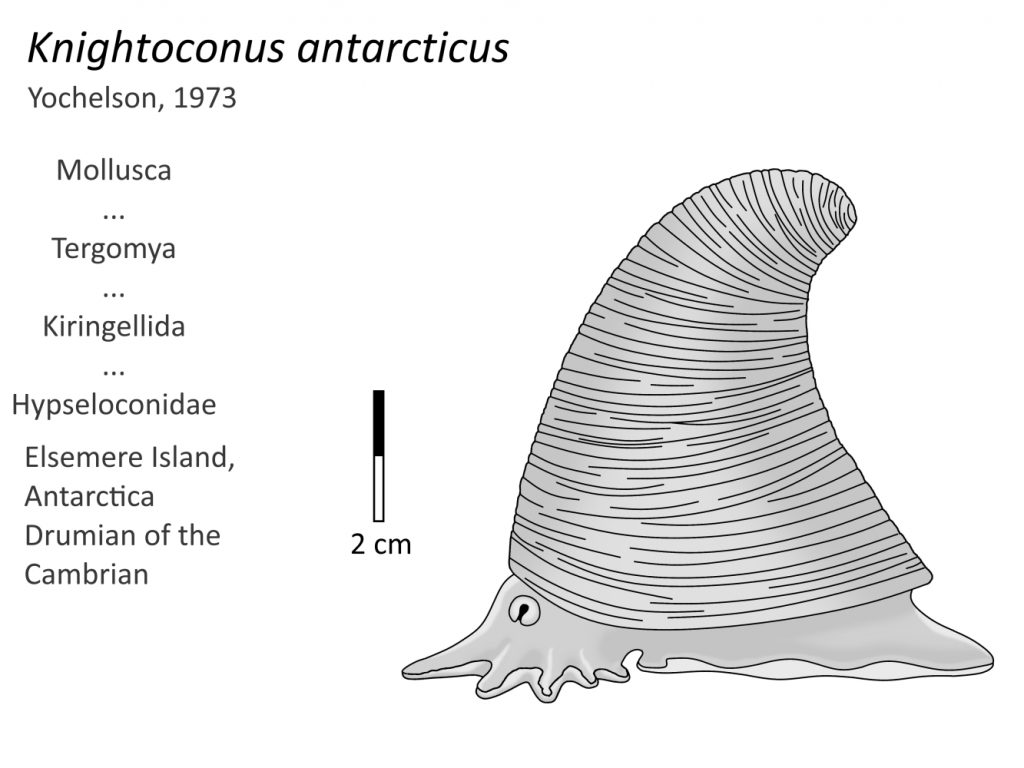

One ancient monoplacophoran that has been seen as a relative of early cephalopods is Knightoconus. Knightoconus didn’t have a true phragmocone; its shell was divided into chambers, but it didn’t have a siphuncle linking them together. Some believe Knightoconus was not related to cephalopods, as we don’t know for sure how a siphuncle would have been formed and other mollusks have septa other than cephalopods. However, others highlight that Knightoconus’s shell is the shape that was hypothesized as what cephalopod ancestors had.

Furthermore, a Knightoconus-like creature could have obtained a siphuncle if a small strand of tissue stuck to the last septum when the animal moved forward to deposit a new septum, leaving a hole in it. These monoplacophorans then likely took advantage of the situation to become cephalopods with fully-functioning phragmocones.

Knightoconus, being a monoplacophoran, probably looked similar to today’s monoplacophorans. Modern monoplacophorans have a large, muscular foot and a mouth lined with small post-oral tentacles. They have no true eyes (1), 2014); since cephalopods have eyes Knightoconus may have. Knightoconus lived on the sea bottom, where it grazed on plat matter or detritus. It could grow to be 2.8 inches (7 centimeters) long.

Now that we know a little about Knightoconus and monoplacophora, let’s get to know Plectronoceras. Here’s some info on what we have of it.

Plectronoceras’s shell was smaller than Knightoconus’s, at only 1.8 inches long. It was shaped differently, too, long and thin and curving backwards. It was this shape that gave Plectronoceras is name, which means, “thin horned one”.

Plectronoceras, as we learned earlier, had a true phragmocone, complete with a working siphuncle. However, studies of its reconstructed shell show that it was too heavy to leave the seafloor simply by regulating the amount of liquid in its phragmocone. Instead, it would give a little jump, and this along with the gas in its chambers would have been enough to escape other predators that were resigned to the bottom.

As a result, Plectronoceras would only have swam through the water when it really needed to; swimming would have been slow anyway, as Plectronoceras couldn’t swim with jet propulsion as most other cephalopods could. Models of Plectronoceras’s shell show it would have had to keep swimming to stay high in the water column, so it would have sunk back down to the bottom in time.

Reconstruct!

Now that we know some info about likely cephalopod ancestors and what ecological niche Plectronoceras filled, we can start to get a picture of what it looked like. We know that monoplacophorans have a large, muscular foot. We know that in cephalopods, this foot is divided into an anterior (or front) and posterior (hind) foot, and that the anterior foot divided further into tentacles while the posterior curled into a tube, the hyponome. This is what modern cephallopods use for jet propulsion, secreting waste, laying eggs, and in shelled cephalopods, the place where liquid is pumped out of the phragmocone. Knightoconus, not having a phragmocone, wouldn’t have needed one of these, so its foot probably looked like that of modern monoplacophorans. However, Plectronoceras may have started to curl its foot into a hyponome, though as stated above it couldn’t have swam using jet propulsion thanks to the shape of its shell.

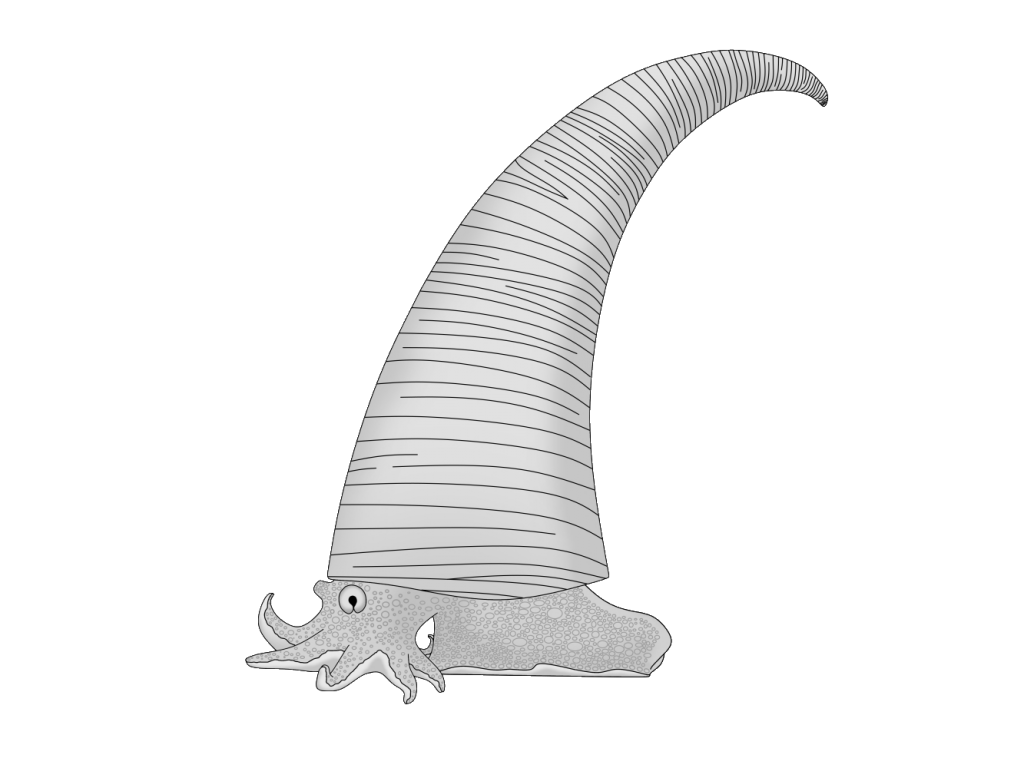

I reconstructed Plectronoceras with an anterior foot divided into ten tentacles, predicted in early cephalopods by embryology (2) and trace fossils (3), a curled posterior foot, a pin-hole eye type like that of the living nautilus (3), a long, gently curving shell, and a little fleshy horn just for fun (4).

Tips for Paleoartists

| Anatomy | Traits | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Shell | Long, thin, gently curving. Slight ribbing. | ||

| Posterior foot | Large, possibly curled. | ||

| Anterior foot | Divided into ten tentacles. | ||

| Eye | Small, likely pin- hole | ||

| Remember: | Plectronoceras lived on the sea floor and had very limited swimming ability. | It was only 1.3 inches (3.2 cm) tall. | |

Sources

Plectronoceras:

https://paleobiodb.org/classic/checkTaxonInfo?taxon_no=12319&is_real_user=1

https://www.ecologycenter.us/early-cambrian/cephalopods.html

https://palaeo-electronica.org/content/2019/2521-cephalopod-hydrostatics

https://www.gbif.org/species/113526442

Knightoconus:

https://paleobiodb.org/classic/checkTaxonInfo?taxon_no=7843&is_real_user=1

Monoplacophora:

https://www.britannica.com/animal/monoplacophoran

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/monoplacophora

Nautilus:

https://incertaesedisblog.wordpress.com/2020/02/16/reconstructing-fossil-cephalopods-endoceras/

https://storage.googleapis.com/conchology-general-images/images/hsn/pdf/1985/8506.pdf